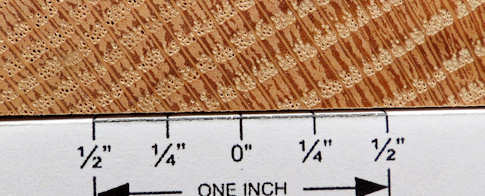

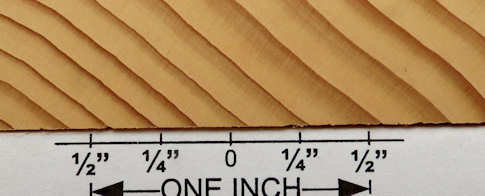

transverse sections showing full sets of growth rings

at the bottom of this page (click) that will take you on a guided tour of 3170 detailed images of 1036 species |

|

|

||

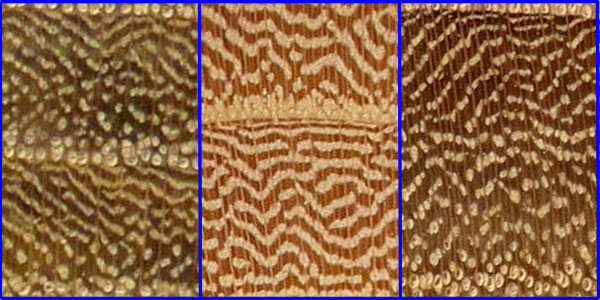

Lebanon cedar |

Russian olive |

||

|

|

||

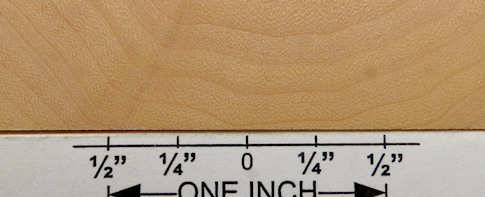

basswood |

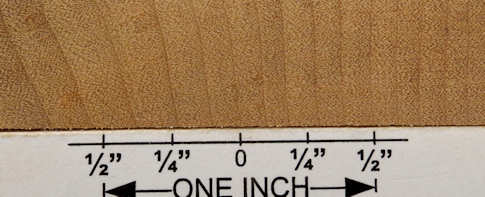

narrowleaf cottonwood |

||

|

|

||

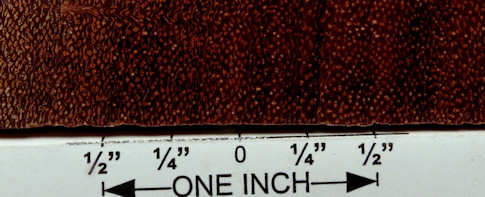

Amazon rosewood |

Madagascar rosewood |

||

|

|

|

|

redwood |

beech |

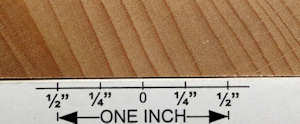

old growth Douglas fir |

|

count and Douglas fir can have a fairly low ring count. These examples are just to show representative example of the COUNTS, not of these particular species | |||

|

|

||

Douglas fir |

old growth Douglas fir |

||

|

|||

ring count in a single piece of wood, which happens if there are years of good growth (wide rings) and years of poor growth (narrow rings). This tree had a lot of bad years in a row there in the middle. In the early and late years it has about 14 rings/inch but in the middle years it has more like 50 rings/inch | |||

|

|

||

black oak |

grand fir |

||

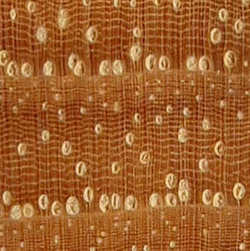

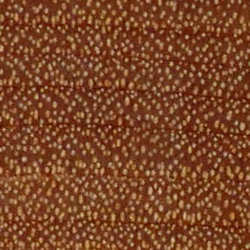

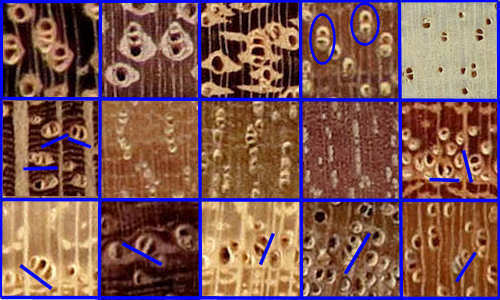

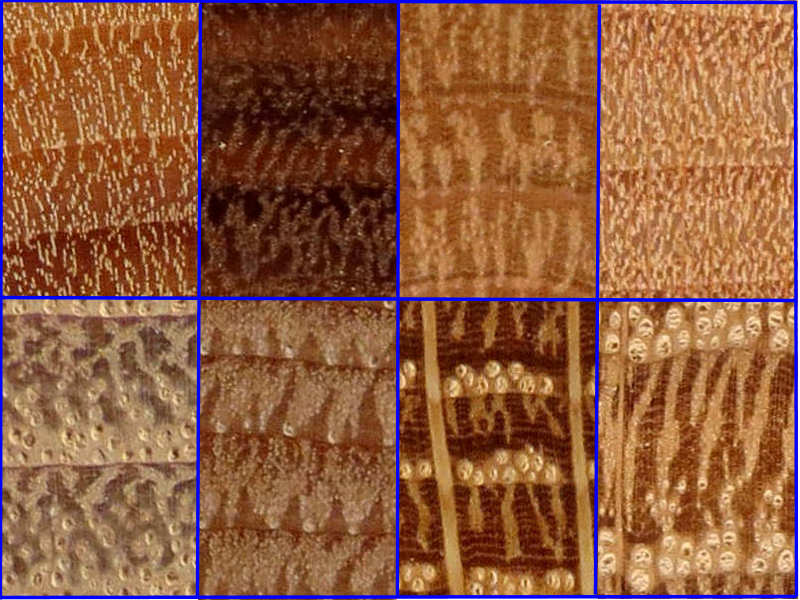

(images are 1/4" square end grain cross sections shown here at 9X) | |||

|

|

|  |

(mockernut hickory) large to tiny pores |

(tropical walnut) medium to small pores |

birch small pores |

apple tiny pores |

|

|

|

(extremely sparse) |

(in various orientations) |

different multiple lengths |

|

|

|

|

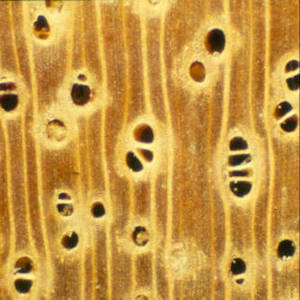

(images are 1/4" square end grain cross sections shown here at 9X) | |||

.jpg) |

%201.jpg) |

%201.jpg) |

.jpg) |

black oak Quercus velutina |

teak Tectona grandis |

black willow Salix nigra |

birch Betula spp. |

(images are 1/4" square end grain cross sections shown here at 9X) | |||

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

%201.jpg) |

quercus velutina |

Quercus mohlenbergii |

catalpa spp |

catalpa speciosa |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

%201.jpg) |

.jpg) |

castanea dentata |

Castanopsis chrysophylla |

Ulmus procera |

Carya tomentosa |

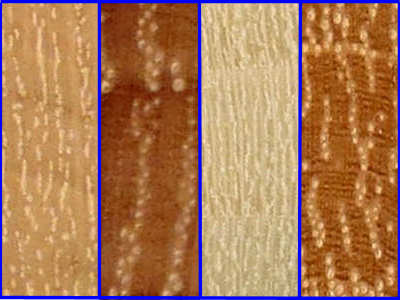

(images are 1/4" square end grain cross sections shown here at 9X) | |||

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Betula spp |

Ostrya virginiana |

Sideroxylon lanuginosum |

Koompassia malaccensis |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Tilia cordata |

Dalbergia monticola |

Umbellularia californica |

Pyrus communis |

(images are 1/4" square end grain cross sections shown here at 9X) | |||

%201.jpg) |

.jpg) |

%202.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Cinnamomum camphora |

Tamarix spp |

Tectona grandis |

Juglans major |

(images are 1/4" square end grain cross sections shown here at 9X) | |||

.jpg) |

%201.jpg) |

%201.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Fagus sylvatica |

Juglans spp |

Pterogyne nitens |

Salix amygdaloides |

| 3170 pics of 1036 species at 12X |

with a mouseover that shows the type of wood and a link that takes you to the anatomy page contining that wood, click HERE |